Blogs

Don’t Ignore the Signs of a Gas Leak in Your Home

It’s hard to ignore the smell of sulfur -- most people agree that it smells like rotten eggs. Propane is naturally odorless. The “rotten egg” smell is purposely added to it as a safety measure in case of gas leaks. Safety is one of our top priorities at Miami Erie Propane, and that’s why we have your best interest in mind when it comes to preventing a gas leak.

A fireplace during the cold winter months can provide the extra warmth and coziness you crave for your home. What if you could have a fireplace without all the hassle and messiness that a wood-burning fireplace creates? With minimal maintenance, heating efficiency, and a cost that is friendly to your family budget, installing and using a propane fireplace is a great way to keep you extra warm and cozy during the frosty Ohio winter months.

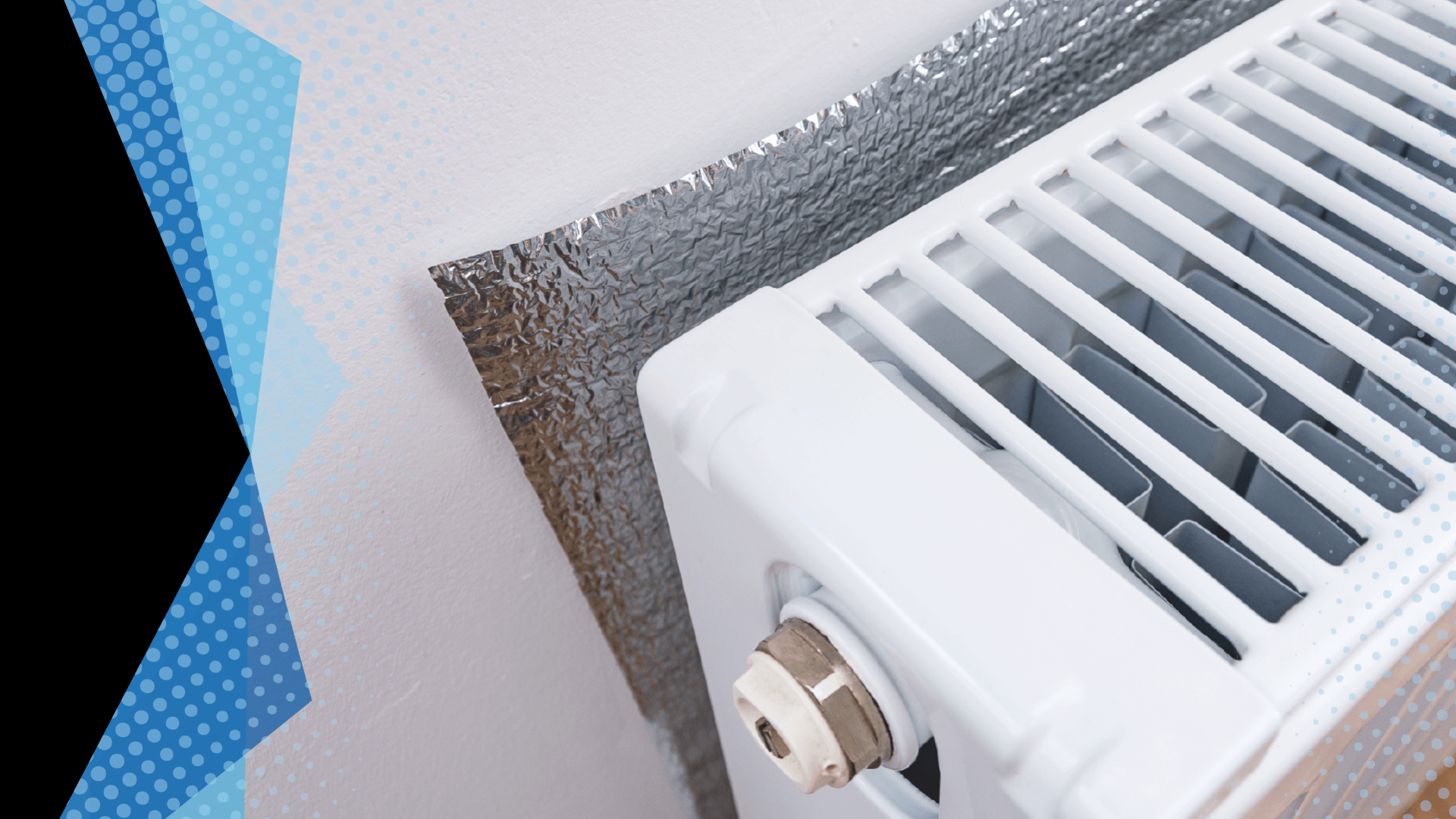

It’s that time of year again when days are shorter, the temperature is lower, and snow is in the forecast. Ohio winters can be harsh, so keep the cold air outside and the warm air inside by properly insulating your home with some DIY solutions.

Think we are full of hot air? According to the U.S. Department of Energy, “Drafts can waste 5 to 30 percent of your energy use.” That’s a lot of money you could be saving when heating your home. At the end of the day, every little bit helps when it comes to saving money.

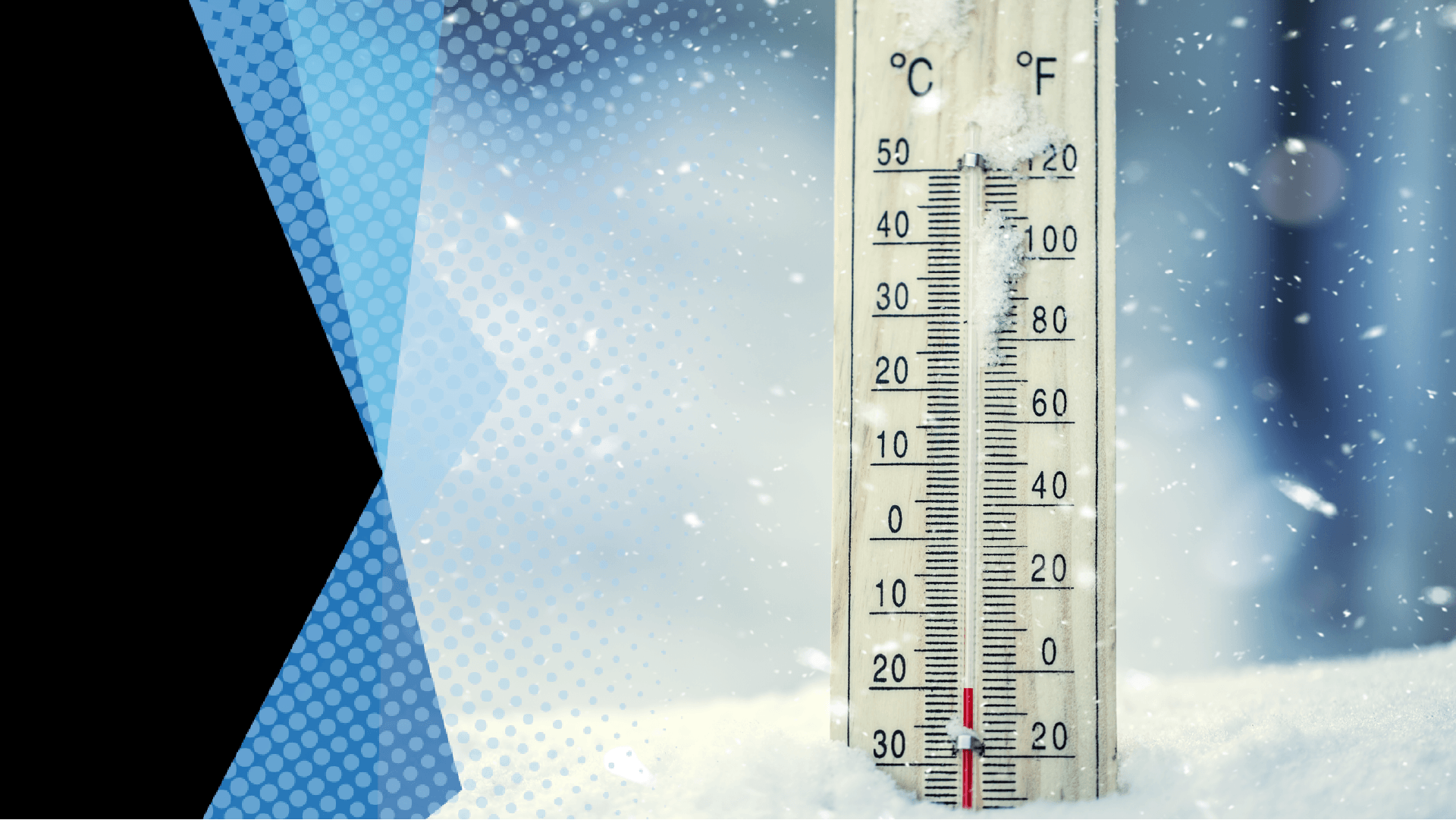

Just a year ago we saw snow storms and long cold spells in Texas that left the state with rolling blackouts that left many in dangerous conditions. Reaching record setting temperatures as low as -2° F, natural gas in Texas literally froze in the pipes which contributed to the blackouts and other problems, such as people losing the ability to cook and heat their homes. Because it's such an important issue, we’ve decided to cover how weather affects fuels and what energy systems are best to keep on hand for extreme weather conditions. We’ll talk about natural gas, propane, and gasoline and weigh just how well each fairs in extreme temperatures.

Propane is an incredibly convenient fuel for all sorts of activities and energy needs. However, it isn’t so convenient when you run out of the stuff mid-way through trying to use it. For this reason, it can be useful to check your tank’s level to see just how much you have left. We will cover a few methods to do just that, as well as, look at autofilling and why you may want to use such services to keep your tank consistently filled. The first method to check your tank’s level is a bit more of a method of estimation, but it works in a pinch. If you heat up water and place it into a cup, you can pour the water from the top of the tank and let it run down the side to figure out the level. Because of the cold temperature of the propane, the hot water will instantly cool when it gets to the height of the tank where the propane sits. Using this method, you can figure out how full your tank is by figuring out where the water cools. The higher up the water cools, the fuller the tank is. This isn’t a perfect solution, but it does a good job of giving you a quick and easy idea of how much propane you’ve got. If you’re looking for a more accurate measurement though, you can’t do much better than a pressure gauge. Pressure gauges provide a read out of the propane tank level in terms of percentages. This lets you know how full the tank is and whether or not it needs a top-off. Many propane tanks come with gauges pre-installed which can usually be found around the fill pipe, but you can also buy a gauge if your tank doesn’t have one. Using a gauge is quite straightforward and allows you to convert to the gas’s weight as well by simply taking the total capacity of the tank and multiplying it by the percentage and 0.01. This will tell you the weight of the remaining propane in your tank. Perhaps you don’t want to spend the time and energy to constantly check and maintain the level of your tank though. This is where auto-filling services can be very useful. Propane delivery companies will often implement a propane tank monitor that will alert them when a tank’s supply falls below a certain level. This relatively new and evolving propane tank monitor technology is also available for personal use where you can monitor your propane levels right from your phone. However, it is most efficient to receive automated propane deliveries from propane retailers, as you’ll never have to worry about running out of gas or making an order for more. Essentially, it requires low effort on the part of the propane user and ensures that you’ll never be caught with an empty tank. Assuming you don’t have autofill services set up, it is very important to keep an eye on your tank not only because of potentially running out, but also to maintain the durability of the tank by preventing internal rusting from moisture that can enter the tank when the pressure is low enough. On the other hand, it’s also important to make sure a tank isn’t too full. After a fillup, the tank should be at about the 80-85% range. This leaves room for temperature fluctuations and allows the propane to safely expand without damaging the tank or sending too much pressure to appliances that use the propane to function. For these safety reasons, automated refills can be quite useful and ensures the longevity of your tank. So, do you monitor your tank and order when needed, or do you go a little further in investing in automated refills? At the end of the day, the choice is yours. Propane is all about using it how you want, and we encourage propane users to make informed choices for themselves on how best they want to do that.

The warmth of Spring is rolling in, and the outdoors and sunshine are calling people to go outside. It’s that time again; time for some outdoor grilling. About 7 out of every 10 US adults own a grill of some variety. However, alongside this popularity, there have been instances where mistakes have been made which have led to negative and unsafe outcomes. We’re here to tell you how to avoid those mistakes and minimize your risk when using a grill or smoker. Before we get into starting the grill, the first important aspect to consider is where the grill is placed. The main thing to look for is wood and other flammable materials that might be close enough to the grill to either heat up from its use or come into contact with large flames should there be a problem with gas concentration. There’s nothing wrong with putting a grill on a deck. However, you’ll want to keep the placement away from wooden railings, walls, and trees to negate the potential for a dangerous situation to get worse. Of course, heat and fire tend to rise, so make sure there is nothing above the grill either which is at risk of combusting or catching fire. Finally, make sure that your grill is on a stable surface and won’t tip over. The last thing we want is to knock over a grill. Once you have placed your grill in a safe spot, the next aspect to consider is the propane tank. Storing a propane tank is usually relatively low risk, but you should try to keep a propane tank as full as possible to maintain pressure and avoid water from leaking in and causing internal rusting. Hooking up a propane tank is relatively simple as well. First, place the propane tank around the base of your grill in a secure spot to where it can’t be easily bumped or knocked over. Next, you’ll take the gas hose, and twist the hose onto the propane cylinder nozzle located at the top of your standard tank. Make sure the hose is connected tightly, and you should be ready for the next step. The next important thing to check is the general condition of the grill. If this is your first time breaking the grill out for the season, it is advised to check under the lid for insects and animal structures like bird nests that may have popped up since the grill’s last use. Once you observe and clear potential hazards, you’ll next want to look at the lower section of the grill to the gas hose. Check for indents and breaks in the hose to prevent leaks. A great way to ensure that all leaks are accounted for is to actually coat the gas line and its two connecting points with a soapy or bubbly mixture. Once the line is covered, turn on the gas and look for bubbles to form. Should you find leaks from the connection points, turn off the gas and tighten up the connections. A broken hose will need to be repaired or replaced. You shouldn’t use your grill until it passes the leak test. After you ensure that your grill is functioning as intended, we can go into safely turning on the grill. The first step is to open the lid so that any excess propane can escape and new propane won’t build up before the grill is ignited. Once the lid is open, you can go ahead and open up the propane tank release valve and turn the knobs of the grill burner to an on state. Now, you can press the ignition button if you have one or light the grill with a flame if you don’t. Doing so will start the grill, and you’ll be ready to go. Shutting off the grill is just as easy and largely involves the opposite process of turning off the burner, turning off the gas, and closing the lid. . That about covers it for our grill safety guidelines. Grilling can be an excellent way to make the best of being outdoors and can undoubtedly cook some great tasting foods, but even seasoned grillers can make mistakes. The important thing to remember is to just be smart and follow the safety recommendations. This will get you the best experience and lifespan out of your grill while protecting people and property in the process. Happy grilling!

It would seem that propane is the most optimal way to limit our ozone footprint. If ecological sustainability is something that you value, but you still require a gas for your daily energy needs like cooking, heating, and electricity, or perhaps you need a gas for your outdoor adventures but don’t want to jeopardize the wildlife around you, consider switching to propane. The ecological advantages might not be immediately apparent, but they will pay off in a massive way for decades to come.

Most people know that propane is an important aspect for many American lives. Whether you enjoy grilling out on a Sunday afternoon or the substance brings energy and heat to your house or farm, propane is a common energy source found in daily life. But do people know how the substance is produced or what makes it so influential in fulfilling its role? Propane can be obtained in two ways. Either it can be extracted from oil after it is drilled from the ground, or it can be extracted as a byproduct of natural gas. Historically, the oil extraction method has been the most prominent. However, the increasing popularity of natural gas processing has shifted the scales in where people’s propane ultimately comes from to about 50/50. Having two extractable sources has helped to keep propane cheap and readily available across the country. The processes are similar in both cases of oil and natural gas methods. Refineries have to separate the lighter gasses like propane from the rest of the chemical mixture in order to isolate the higher-octane fuels and collect them for distribution. Although the goal is the same for both extraction methods, the processes do differ due to the unique chemical makeup of each fuel source. When oil is being refined, there are multiple stages in the process where petroleum gasses are isolated. These petroleum gasses make up about 1-4 percent of processed oil, propane being one of the most common as well as butane and isobutane. A process called fractional distillation is used to separate out these components when they are in their liquid form. During fractional distillation, the unseparated mixture is subjected to cooling and pressure which utilizes the different boiling points of each hydrocarbon. This effectively isolates different components further by turning them from a liquid to a gas, allowing the lightest hydrocarbons to rise to the top as purified products, which can then be collected for distribution. Extracting propane out of natural gas also requires fractioning out individual parts, but it yields a higher average of 5% propane per yield. However, not all natural gas wells are optimal for collecting propane. Unlike oil or gas wells where natural gas is present and can be free-flowing in its raw state, condensate wells provide free flowing natural gas mixed together with a variety of other hydrocarbons. Natural gas processing actually removes these hydrocarbons known as “wet gas” to reduce the potential for rusting within its piping. In the natural gas world, dry and pure are highly preferred. To remove these more vaporous gasses which include propane, a similar temperature and pressure method is used to the oil method to separate the condensate from the natural gas mixture. Any residual oil is also separated out because of it’s relatively high weight. Once condensate is captured, it is further divided into its parts with a separator. Once propane is extracted, it is cooled to below -44°F for transport. Liquified gas is 270 times more dense than it’s gas version which improves space efficiency significantly. A rotten egg-like odor is also added to the gas before retail to add a safety system to an otherwise odorless and colorless gas. This helps propane users to identify a leak in the unlikely case that there is one. Extracting individual compounds in their raw form can be quite the science experiment. It takes a strong knowledge of each compound and process to pull it off correctly and efficiently. Commercial gasses are subjected to quality control standards, so prospectors really have to know what’s in their product before relaying it on to distributors and customers. For those outside of the industry though, this means that propane is safe and pure and can be trusted to run propane-fueled equipment efficiently without interference from other types of gas. The process ensures that you get the optimal bang for your buck, so you can spend more time worrying about flipping burgers rather than the fuel that provides the heat.

It’s no secret that gasoline and diesel are the most prevalent automotive fuels on the market. However, there is one fuel that largely flies under the radar when it comes to propelling vehicles. Propane, also known as LPG, is a commonly utilized automotive fuel often used by public fleet setups such as police vehicles, school buses, delivery trucks, taxi services, and other bulk transportation systems. Why do large transportation services opt for propane fueled vehicles? There are a variety of factors that come into play. Most notably, propane powered vehicles burn much cleaner than their more popular gas and diesel counterparts. Free of methane and other toxic hydrocarbons, propane-based fuel systems help to improve environmental factors both for the air and water quality of local residents. It also has an impact on suppressing damage done to the Earth’s ozone. Unsurprisingly, the ecological benefits of propane help to garner state, local, and federal tax incentives that help to bolster cleaner uses of energy in the operation of vehicles while being a huge benefit to the owners of these vehicles. These tax incentives come out of the tax rate at purchase and helps to improve the costs of going with propane. So, does this give propane more bang for its buck? The answer is somewhat complicated, but is largely a yes. Propane offers much more energy security than petroleum as it is produced domestically and therefore is not subject to the complications of international supply chains and transportation costs. This ensures that propane is more consistent in its availability and price point. The price of propane is also consistently lower on average than gasoline, ranging from 30% to 50% cheaper per BTU (unit of energy measurement). This means that propane is almost always the cheapest route, especially when adding on tax incentives. Additionally, propane helps with lowering maintenance costs, as it is less straining on engines making it quite a cost effective option. So what’s the catch? The reason propane isn’t always the cheapest stems from the upfront cost associated with buying a propane-running vehicle or outfitting a vehicle to use propane. These upfront costs range in the thousands and are closer to that of diesel engines. But, unlike the majority of diesel vehicles, these costs can be easily offset in the long run thanks to propane’s cost efficiency, the vehicle’s greater lifespan, and a lesser need for maintenance. The average fleet vehicle with it’s high rate of use can often have a payback period of 12 months or less, which means any further driving will result in direct savings. Residential vehicles will most likely have a longer payback period unless driven on a frequent basis but will almost certainly make its money back by the end of its lifespan. This translates into direct savings in the long run all while burning cleaner fuel. So how does one obtain a propane powered vehicle? Propane vehicles come in two varieties: dedicated which runs purely on propane and bi-fuel which allows the user to utilize both propane and gasoline by switching between the two. Vehicles can be converted to use propane by certified technicians or you can buy a vehicle with a certified fuel system already installed. You can easily track down such vehicles by navigating the Alternative Fuels Data Center on the Department of Energy’s website. If you’re looking for a way to cut costs and your ecological footprint while trying to meet reliable transportation needs, take a look into propane. It will undoubtedly be worth the effort.